<strong>Guided By Birds: Avian data to guide Clayton Hill restoration</strong>

by Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy

Forest restoration is a moving target. To measure the impacts and progress of restoration efforts practitioners must choose certain quantifiable elements of an ecosystem that can indicate habitat quality. For the restoration site in Frick Park known as Clayton Hill, we have been monitoring bird species during the summer breeding and fall migration seasons to interpret the habitat quality of the areas we are working to restore. Metrics about avian populations provide us with an honest evaluation of the function of our restoration sites because they are not something that we can directly control (as opposed to things like plant species diversity, or forest canopy cover which we actively change through native species plantings). Now, two years into our avian monitoring process our partners at the Western PA Conservancy (WPC) have compiled our first summary report about the bird species that rely on Clayton Hill for fall migration and summer breeding habitat.

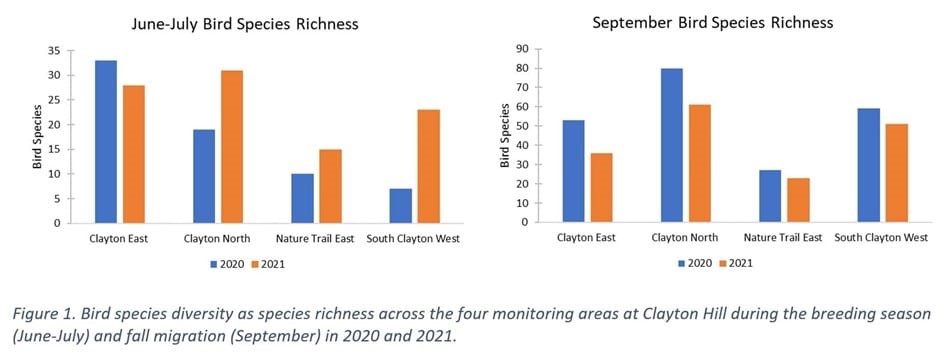

To monitor the birds on Clayton Hill, we divided the whole restoration area into four monitoring units (Fig 1). We divided the site this way to control for topographic features such as aspect (north facing vs south facing), elevation (ridge top vs creek bottom), or slope (flat land vs steep hillside) that might inherently attract different bird communities. By monitoring these areas separately, we can also determine if specific units seem to be increasing or decreasing in avian habitat value. In turn, this helps us determine priorities for future restoration efforts.

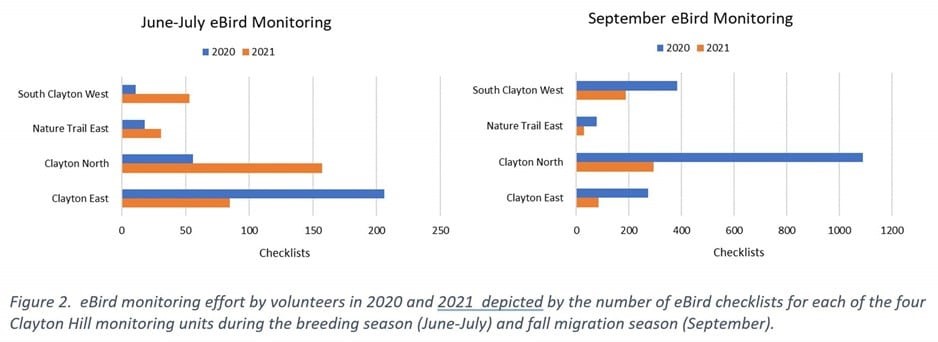

While it may seem straightforward at first, any ecological monitoring is a time-consuming task. Good data is dependent on repeated sampling, and it can be challenging to acquire the human-capacity required to collect all the information we’d like. Fortunately, through the eBird app we can utilize the observations of volunteer citizen scientists to help monitor the Clayton Hill restoration area. eBird is a product of The Cornell Lab or Ornithology, and it provides a platform that birders everywhere can use to record their bird observations. Partners from the WPC and Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s (CMNH) Powdermill Nature Reserve established ‘eBird hotspots’ for each Clayton Hill restoration unit. By logging bird observation to these eBird hotspots, bird-watching park users are able to perform bird surveys on their own time in our specific monitoring units. These citizen scientists are imperative for the continued monitoring and successful progress of our ecological restoration work.

In 2020 and 2021, researchers and citizen scientists observed 116 species of birds utilizing the Clayton Hill restoration area during the breeding and fall migration seasons (Table 1, below). The Clayton North monitoring unit had the highest species richness (the highest number of unique species observed) in 3 of the 4 monitoring periods (Figure 1). We saw the lowest species richness in the “Nature Trail East” unit, but also had the fewest number of checklists completed in this area (Figure 2). Total bird abundance (the number of individual birds observed) varied across sites and seasons, however, survey effort was also inconsistent across seasons, which likely added variance to these early data. For more details, you can view the full report here.

While these data are interesting on their own, the most useful data for evaluating restoration will come from our ability to identify trends over time. These first two years of data are only the baseline numbers that we can use for future comparisons. In the coming years our dataset will grow alongside our restoration plants, and as it does we hope to discover new insights about the changing quality of the Clayton Hill habitat. In the meantime, patience is a requirement. Meaningful restoration occurs on the timescale of years to decades, as it takes plants that long to become established and even longer for them to serve their full suite of ecosystem services. As the native species that we’ve added to Clayton Hill grow, we hope they will provide food and improve habitat for a wide range of bird species. But if we grow it, will they come? Although birds have been observed to show remarkable memory for quality habitat along their migration routes (Mettke-Hofmann and Gwinner. 2003), they first have to discover a site worth remembering. For this reason, it’s important that we’re always looking for opportunities to scale up our restoration efforts and improve connectivity between forest sites.

Already, partners who’ve been working on the Clayton Hill restoration project are using initial observations of avian habitat quality to inform our next management steps. An invasive annual grass called Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) has been steadily expanding through much of Clayton North and Clayton East, and an alarm has been raised that this grass is causing trouble for ground-dwelling migratory songbirds. Given this reality, we are focusing on the habitat needs of those species when designing future projects and workplans – for instance planting shrubs and perennials that will stand up (literally) against the crushing weight of a field of bolting stiltgrass (below).

At Clayton Hill, we are several years into our work facilitating regeneration of native forest habitat but we are still decades away from our goal of achieving a stable, productive, and biodiverse urban forest ecosystem. The presence and abundance of bird species that thrive in healthy native forest communities will keep us honest about our progress, while the tireless work and passion of our many partners keeps us all moving forward in the best ways that we know how. If you’re interested in learning more, we invite you to come out for our fall World Migratory Bird Day event at the Frick Environmental Center on October 8. We also welcome all birders to submit an eBird checklist using our Clayton Hill Hotspots!

This project would not be possible without the joint efforts of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Allegheny GoatScape, the Allegheny County Bird Alliance, and the dozens of citizen scientists, volunteers, and donating organizations who’ve contributed to this project. The Clayton Hill Restoration work has been supported by funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Federation, the Pittsburgh Foundation, the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and donations from Pittsburgh’s park users.